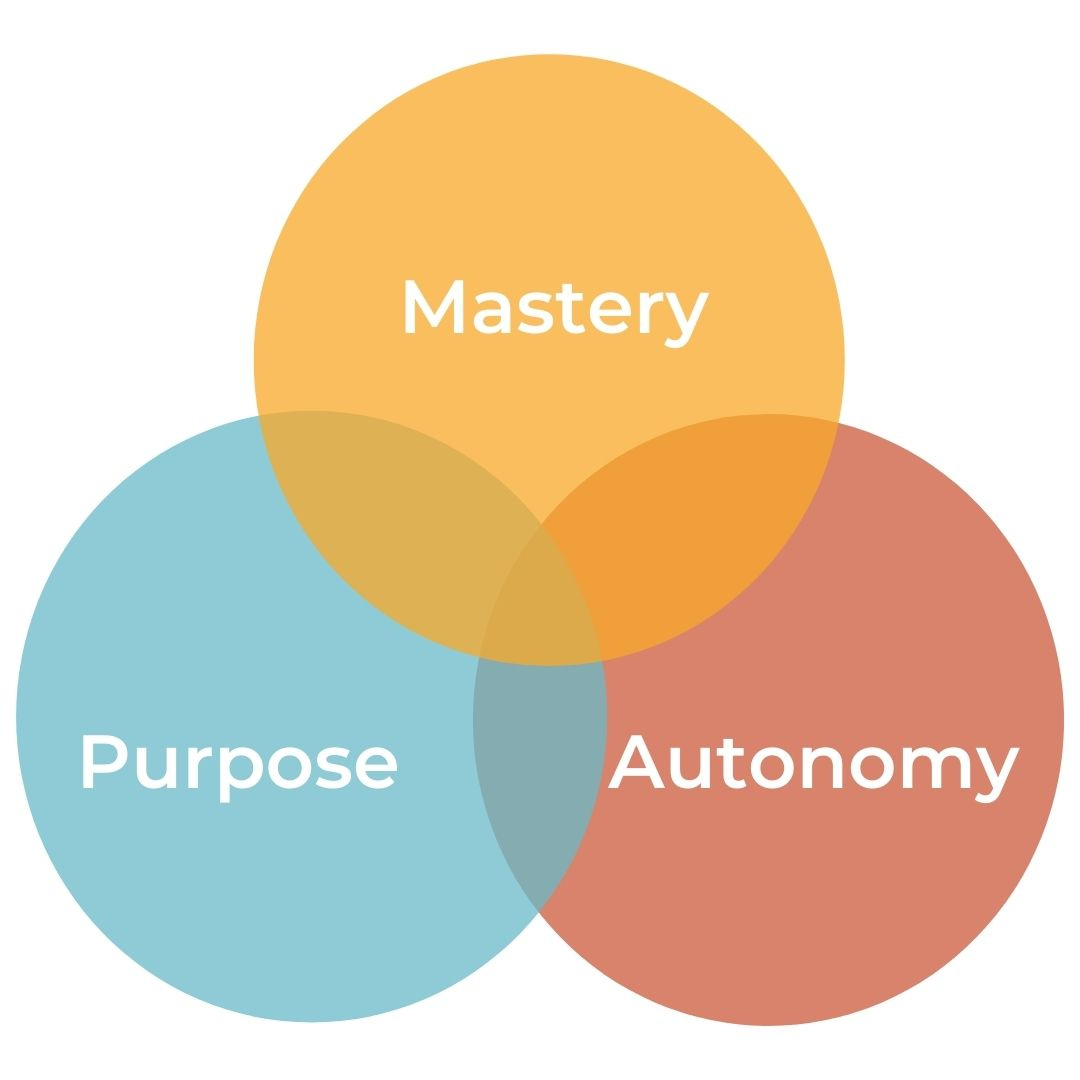

Understanding Employee Motivation: Dan Pink’s Secrets of Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose

Dan Pink’s Motivation Secrets: How Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose Drive Success

Motivating people isn’t just about offering raises or bonuses—it’s about tapping into what truly drives them. In "Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us," Dan Pink flips traditional motivation theories on their head. His research shows that the old carrot-and-stick model—rewarding good behaviour and punishing bad—works only for simple, repetitive tasks. But for modern work that requires creativity, problem-solving, and innovation, motivation comes from within.

I first read about Dan Pink’s work in 2013 when I read “To Sell is Human” and realised all our meeting presentations, convincing leaders to provide support and funding for product work, convincing teams to work on and deliver a product, this was all sales work. We were all selling, even without the title. So reading Drive a few years later, really solidified what makes us as humans tick.

In Drive, Pink focuses on Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose when looking at what motivates people.

Let’s dive into what they are and how companies can use them—whether driving everyday performance or leading large-scale transformations.

1. Autonomy: The Freedom to Own Your Work

People thrive when they have control over their work. Autonomy isn’t about a complete lack of structure—it’s about giving people the freedom to choose how they get things done. This sense of ownership makes employees feel empowered and more motivated to succeed.

"Autonomy without alignment is Chaos" to quote Herry Wiputra at the recent Product-Led Alliance Summit in Sydney (2024).

Exactly!

Provide context, direction and seek alignment. Then introduce autonomy for high performing teams.

Example:

At Atlassian, the Australian software giant, employees get “ShipIt Days” where they can work on any project they’re passionate about for 24 hours. The result? Solutions to stubborn technical problems and brand-new product features—all because employees were given the autonomy to explore their ideas.

How to Apply It:

Give employees flexible schedules—let them choose when and where they work.

Delegate responsibility by allowing teams to own entire projects and make decisions independently.

2. Mastery: The Drive to Get Better at Something Meaningful

Humans are wired to want to improve and grow. When people see progress in their skills, they feel energised and motivated. But mastery is about more than just hitting goals—it’s about embracing challenges, learning from setbacks, and continuously improving. Pink emphasises that mastery thrives in environments with a growth mindset—where failures are viewed as opportunities, not dead ends.

Example:

Google’s 20% time policy allows employees to spend 20% of their working hours on side projects that interest them. This freedom to develop new skills has led to groundbreaking products like Gmail and Google News. Employees weren’t just doing their jobs—they were mastering new capabilities while building things that mattered.

How to Apply It:

Offer upskilling programs like workshops or mentoring.

Celebrate progress milestones, not just big wins—small achievements build momentum.

3. Purpose: The Need to Do Work That Matters

People don’t just want to clock in and out—they want to know that their efforts contribute to something bigger than themselves. When employees feel that their work aligns with a greater mission, their motivation skyrockets. Purpose gives meaning to even the most routine tasks, turning work into something fulfilling.

Example:

At Patagonia, employees know that the company’s mission is to save the planet. Every product they help design or sell contributes to environmental sustainability. This alignment with purpose keeps employees engaged, even during busy or challenging times.

How to Apply It:

Regularly share stories of how your company’s work makes a difference in the world.

Connect individual roles to the broader mission—help employees see how their contributions matter.

Why Carrots and Sticks Don’t Work Anymore

Pink’s research shows that extrinsic rewards—like bonuses or promotions—can be effective for tasks that require no creativity. But they often backfire for cognitive work by reducing intrinsic motivation. For example, offering a reward for brainstorming ideas can shift focus away from the joy of problem-solving and toward earning the reward.

In workplaces everywhere, intrinsic motivation—the desire to perform well because it feels good—is far more effective. When organisations foster autonomy, mastery, and purpose, people become self-motivated, more innovative, and better equipped to handle challenges.

How did we think about Human Motivation before 2000?

Before Dan Pink’s insights on intrinsic motivation through autonomy, mastery, and purpose, psychologists primarily focused on extrinsic motivators—like rewards and punishments—as the key drivers of behaviour. Much of the early research assumed that incentives such as money, promotions, and recognition were the most effective tools to motivate people.

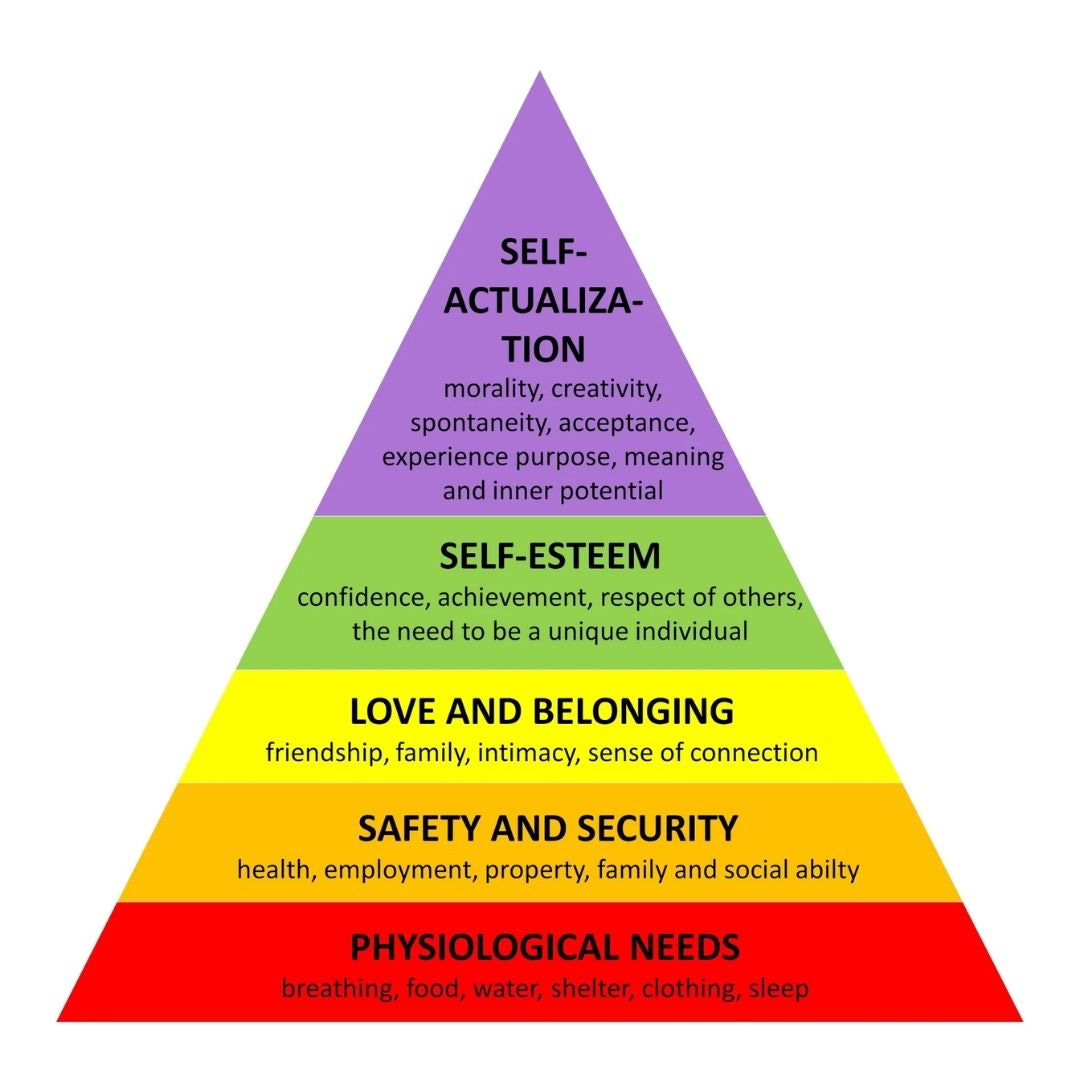

1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943): Climbing the Motivation Pyramid

Abraham Maslow proposed that people are motivated by a hierarchy of needs, starting with the most basic survival needs and moving toward more abstract aspirations like personal fulfilment. He argued that motivation stems from meeting these needs in sequential order—you can’t focus on self-improvement if your basic needs aren’t met.

Maslow’s Pyramid Levels:

Physiological Needs: Food, water, shelter.

Safety Needs: Job security, financial stability.

Love and Belonging: Relationships and social connections.

Esteem: Recognition, status, and self-worth.

Self-Actualization: Achieving one’s full potential.

A person working a job they don’t enjoy may still be motivated if it provides a steady income and job security. Once those basic needs are satisfied, however, they may look for work that offers recognition and personal growth opportunities.

Maslow’s theory assumes that people must satisfy lower-level needs before focusing on higher-level goals (e.g., creativity and purpose). However, real-world behaviour shows that people don’t follow this rigid sequence. Employees in tough situations (like low pay or job insecurity) still pursue fulfilling work and creative endeavours—contrary to Maslow’s assumptions.

Examples:

Artists and entrepreneurs often pursue their passions despite financial hardships, challenging the idea that basic needs must always come first.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many healthcare workers—despite unsafe working conditions—felt motivated by a sense of purpose to help others, skipping the "safety" layer of Maslow’s pyramid.

Research Insight:

Studies on workplace motivation show that people can seek meaning and personal growth even when their basic needs are unmet. This demonstrates that purpose-driven work motivates people beyond financial security or status.

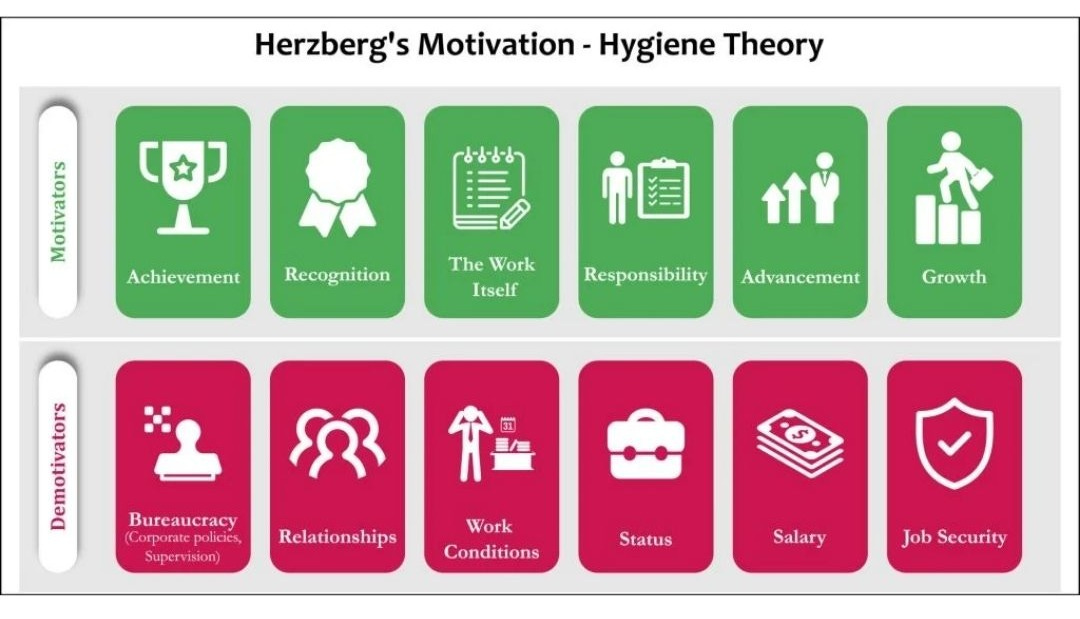

2. Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory (1959): Job Satisfaction vs. Dissatisfaction

Frederick Herzberg identified two types of factors that influence workplace motivation: Hygiene factors and Motivators. He believed that these two sets of factors are distinct—removing dissatisfaction doesn't necessarily create motivation.

Two Key Factors:

Hygiene Factors: Salary, job security, company policies, working conditions. These factors prevent dissatisfaction but don’t create lasting motivation.

Motivators: Recognition, achievement, personal growth, and responsibility. These factors drive engagement and job satisfaction.

An employee may not be unhappy with their salary and benefits, but what really motivates them is the opportunity to take on challenging projects and learn new skills.

Herzberg’s theory overlaps with Pink’s focus on mastery, but Herzberg puts job satisfaction as the core motivator, whereas Pink emphasises a broader sense of purpose and autonomy in addition to mastery.

Herzberg suggested that hygiene factors (like salary) prevent dissatisfaction, but only motivators (like personal growth) drive real engagement. In reality, the distinction between the two isn’t so clear. Research shows that salary and rewards sometimes do impact motivation—especially in competitive industries where pay is tied to performance.

Examples:

Tech companies like Google and Meta offer both high salaries and personal growth opportunities, recognizing that competitive pay is still important in retaining top talent.

Performance bonuses in sales roles show that money can directly influence motivation, especially when employees are driven to outperform peers.

Research Insight:

While intrinsic motivators matter, extrinsic rewards can also motivate, especially when employees feel fairly compensated compared to their peers. Herzberg’s strict separation of hygiene and motivators doesn’t always hold up.

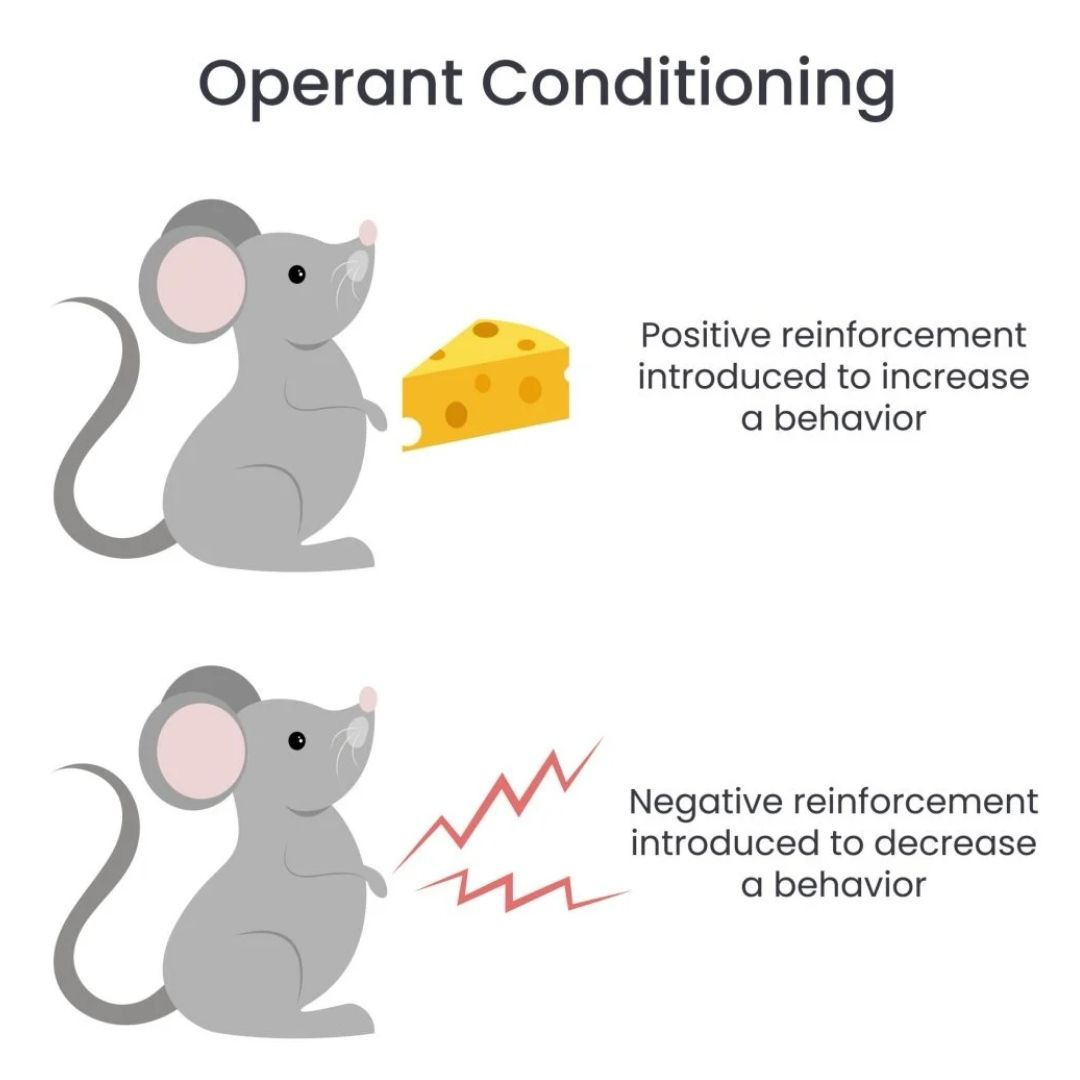

3. Skinner’s Operant Conditioning (1938): Rewards and Punishments

B.F. Skinner, a behaviourist, believed that behaviour is shaped by rewards and punishments—a process called operant conditioning. According to Skinner, people are motivated to repeat behaviours that lead to rewards and avoid behaviours that result in punishment.

Operant Conditioning examples:

Positive Reinforcement: A company offers bonuses for hitting sales targets, encouraging employees to work harder.

Negative Reinforcement: Employees might receive warnings or demotions for underperformance, which motivates them to improve.

Skinner’s behaviourism emphasises that people respond to rewards and punishments. However, studies reveal that extrinsic rewards can backfire for tasks requiring creativity, reducing intrinsic interest in the work itself. When rewards are expected, they shift the focus to external incentives, leaving people less engaged in the actual task.

Pink argues that while extrinsic motivators like bonuses can work for simple, repetitive tasks, they can actually reduce creativity and intrinsic motivation for cognitive, innovative work. Pink focuses on building environments where people want to excel rather than being pressured by rewards and punishments.

Examples:

The Candle Problem Experiment (Karl Duncker): Participants were asked to solve a problem using limited materials. When rewarded with money, participants performed worse than those without incentives, suggesting that external rewards hinder creative thinking.

Netflix’s unlimited vacation policy gives employees the autonomy to take time off as needed, without tracking. This policy shows that trust and freedom, not punishments or rigid rules, build engagement.

Pink’s theory fits better for complex, modern work—people are more motivated by freedom and mastery than by external rewards or fear of penalties.

4. Expectancy Theory (1964): Motivation through Expected Outcomes

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory suggests that people are motivated when they believe their effort will lead to a desired outcome. The theory breaks motivation into three elements:

Expectancy: The belief that effort will lead to good performance.

Instrumentality: The belief that good performance will result in rewards.

Valence: The value placed on the reward by the individual.

An employee will feel motivated to work overtime if they believe that it will result in a promotion or raise and that the reward is worth the extra effort.

Expectancy theory assumes that people behave rationally, motivated by a clear link between effort, performance, and rewards. However, real motivation is often more complex. People might choose to put in effort even when outcomes are uncertain, especially when driven by purpose or personal interest.

Examples:

Open-source developers work on software projects like Linux without any guaranteed rewards, motivated by personal mastery and a desire to contribute to the community.

In creative fields, such as music or art, people often pour effort into projects that may not yield any financial reward, driven by passion and meaning instead.

Research Insight:

This shows that people aren’t always calculating rewards—sometimes they work hard for intrinsic reasons like mastery or purpose, beyond what expectancy theory predicts.

5. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y (1960): Different Views of Motivation

Douglas McGregor described two contrasting views of employees in the workplace:

Theory X: Employees dislike work and need strict supervision and external rewards to stay motivated.

Theory Y: Employees are self-motivated and can thrive when given freedom and responsibility.

A Theory X manager might use closely monitored KPIs and strict rules to keep employees on track. In contrast, a Theory Y manager might give employees autonomy and trust, believing that they will naturally strive to do good work.

Pink builds on the Theory Y approach but goes a step further by identifying the specific elements—autonomy, mastery, and purpose—that fuel self-motivation in today’s workplaces.

Agile teams in tech companies thrive on autonomy and collaboration, aligning with Theory Y principles. But during crises or high-pressure projects, more structure and oversight (Theory X) can be helpful.

Amazon’s warehouse operations rely on strict rules and performance metrics to meet tight delivery timelines, while their product teams enjoy autonomy to innovate and experiment.

Effective leadership requires flexibility—balancing autonomy with accountability, depending on the team and context. Pink’s focus on autonomy, mastery, and purpose offers a middle ground, helping leaders align freedom with structure.

Key Research Supports Dan Pink’s thinking about motivation

Several studies have reinforced Pink’s ideas about intrinsic motivation:

Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory (1970s):

Research by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan found that intrinsic motivators—like autonomy and competence—boost performance more than external rewards. Their work laid the groundwork for Dan Pink’s model.Google’s 20% Time Policy:

Google discovered that employees were more innovative when given autonomy to work on side projects. Products like Gmail and Google News emerged from this policy, proving that freedom fuels creativity.MIT Studies on Incentives:

Researchers at MIT found that higher monetary rewards decreased performance in tasks requiring creativity and cognitive thinking, aligning with Pink’s claim that external incentives can hurt innovation.

The Evolution to Dan Pink’s Model: Why It Stands Out

Earlier motivation theories emphasised extrinsic motivators like paychecks, benefits, and recognition. These models worked well for industrial-era tasks that were straightforward and repetitive. However, as the workplace has evolved to focus on creative problem-solving and innovation, these theories fall short. Faced with rapid change, organisations need creative, innovative and empowered teams to solve complex problems.

Why Pink’s Model is Different:

Intrinsic Motivation: Pink argues that people are motivated by things that money can’t buy—the freedom to choose how they work (autonomy), the desire to improve (mastery), and the need to contribute to something bigger (purpose).

Modern Work: Pink’s ideas align with today’s emphasis on agile teams, flexible work environments, and purpose-driven companies.

How to Apply Pink’s Motivation Model During Major Transformations

Let’s say your company is undergoing a major transformation—like moving from a traditional structure to the Product Model. How do you keep employees motivated through such a disruptive change?

1. Autonomy in Transformation:

Give product teams the freedom to decide how they implement agile processes. For example, let them design their own sprint cadences or choose which tools to use. This helps employees feel ownership over the change instead of feeling forced into it.

2. Mastery in Transformation:

Offer opportunities for employees to learn new skills, such as training in product management or certifications in agile frameworks. As they grow, they’ll feel more confident and excited about their roles in the new structure.

Learn from me. I created a course for people new to Product Management aligned with the learning outcomes created by product greats. Spend 2 days learning from me - either face to face or via Zoom - with ICAgile Certified Professional in Product Management (ICP-PDM).

3. Purpose in Transformation:

Communicate the “why” behind the change—show employees how the new Product Model will allow the company to better meet customer needs and deliver more impactful solutions. Help them see the transformation as part of a bigger journey that benefits not only the business but the people they serve.

Want to Understand the Human Side of Change?

Learn from me!

Having lived through multiple transformations and changes, I’m a certified instructor of the APMG Change Management course.

You’ll learn the behavioural science of change, the processes needed to make change stick and how to inspire and create the support for change through understanding human motivation, neuroscience and psychology.

Transformations are never as simple as changing a system, process or tech. The human side is crucial to success.

Ask me how I can help. Send me an email at irene@phronesisadvisory.com

Are you new to Product Management and want to learn from me?

I created a Course. For people new to Product Management.

Aligned it with the Learning Outcomes created by Product greats like Jeff Patton and others. Had it certified by the globally recognised ICAgile.

Choose to spend 2 days learning from me - either face to face or via Zoom - withICAgile Certified Professional in Product Management (ICP-PDM).

And if you’re looking for a sneaky discount, send me an email at irene@phronesisadvisory.com